Don't Take Any Shit from a Machine

This is a bit of a callback to classico Outlandish Josh posting. I’m pulling up stories from the early aughts, but hopefully it’s fun and you stick with it; I promise there’s a contemporary tie-in at the end.

Twenty years ago when I was working in politics full time, I was also going out to the Oregon Country Fair in the summers. It’s one of the older and better hippie festivals. In 2004 I helped organize a voter registration drive there, and happened to get a chance to meet and chat with S-tier guru legend Stephen Gaskin. In spite of this also being in the shall we say spicier era of my blogging career, I never wrote this particular anecdote down.

The Oregon Country Fair is a massive hippie festival held every summer in a beautiful wooded area outside Eugene where I grew up. There are around 1000 different stalls that get set up along a massive figure-eight path, and over 30,000 people attend.

The real deal is you need to have a job there to be able to be a part of the action. It’s open to the public from like 10am to 6pm, and tens of thousands of people will come and it’s a big hairy Height Asbury/Dead show parking lot scene in the woods. Crafts and food. Music and art. Then they sweep out the public and the 5,000-ish people who are running the event, who have a booth there, or are otherwise connected enough to make the cut as “Fair Family,” who are camped out for the weekend have the place to themselves. They (we) have a giant fucking party. Which is tremendous fun.

My way in was working at a food booth called the Holy Cow, which did heavily marinated/sauced tofu and rice/veggie dishes. They were well known and loved because the stuff really was delicious. The line for dinner (after the public was swept out) was often honestly longer than the line for lunch when the whole scene was packed. We stayed open until midnight to serve fair family, and opened at 6 or 7am with a special family-only breakfast menu of home fried potatoes and bagels w/cream cheese (which paired really well with the BBQ tofu if you wanted it). We also had coffee.

This was all run out of a sprawling wooden structure built around and into a pretty good sized stand of maple or oak trees; there was a whole kitchen with propane rocket burners, giant wooden insulated coolers packed with block ice, and a whole elevated floor/french drain, cutting surfaces, and sinks to keep food production humming and sanitary. The roof had like 10 giant blue barrels for water, which a truck would rumble by and top up early every morning.

It was a significant operation. My first year I actually earned my stripes by going out with my buddy (who got me the job) to work with the master hippie carpenter who maintained the physical infrastructure. We spent several weekends running up to the festival making sure everything was ready. He was an awesome dude; super-competent but also super-kind, really made everyone and everything around him brighter.

This was also a nice introduction to the Fair experience because it meant I only had to work a couple shifts in the shop during the event, so had more of my time to myself to run around and have fun. Sadly, while I’m a possibly competent hippie carpenter, there are many more capable volunteers for that slot, so in subsequent years I worked two four hour shifts every day. Usually one in the morning and one at night if I could swing it.

Anyway, so one evening in 2004 I’m on the front register — I’m good with people so I usually worked up front unless something else more urgent needed doing. It’s just after the sweep, sunset coming through the trees, as the dinner crowd starts picking up, and I notice there’s a gaggle of people crowding around some dude. Usually crowds gather around musicians, but this was just some old head holding forth. I was curious what was going on and then someone said his name and that’s when I realized it was Stephen Gaskin.

I won’t summarize his wikipedia article, but Stephen Gaskin was one of the realer ones to come through the ‘60s. I had discovered his legacy a few years earlier and gotten a pirate e-text of his book Monday Night Class, which is a transcript of a bunch of lectures he did in San Francisco between 1968 and 1970. They really resonated with me; something in his alchemy of the practical with the psychedelic and mystical; before he was Height Asbury royalty he had been a US Marine and served in Korea. He really got shit done. Plus just a great raconteur, he knew how to turn a phrase.

So naturally while I was taking tofu dinner orders I was trying to follow what they were talking about over in that group. The only snippet from that night that stuck with me was just as they were starting to break up and a bright eyed guy asked, “Stephen, what do you think... ahhhh... about matters of the spirit?”

I’m obviously paraphrasing now with a ton of distance, but the answer was something like:

“Well, you know, what I’ve always said is that I’m looking for… you know this metaphor might not be so good anymore, but you remember how back in the day IBM used to program computers with punch cards? Little cards with holes in them that you’d stack up thousands at a time and that would tell the computer what to do? Well you ask me about matters of the spirit, I’ll tell you what I’m interested in is finding the places where those cards — you know they used to keep them in great long drawers like a library card catalog —finding places where one hole goes all the way clean through.”

After that they were gone. The little clutch broke up and went their separate ways. I wrapped my shift a few hours later and went out to meet my friends at our camp back in the woods, stayed up all night doing [redacted], and went straight back to work at 6 or 7am. It was kind of brutal to roll onto a shift while your brain and body are still coming down and you haven’t slept, but I was also 25 at the time, and tended to find that drinking coffee and singing songs and making people’s faces light up with freshly toasted bagels was more than enough to bring my energy back around.

Who should show up in the breakfast line but Stephen Gaskin. He was with his partner and they were like a really endearing older couple out on an adventurous vacation. Just wanted bagels and coffee but if I remember right I got him to take a scoop of the BBQ tofu, which he absolutely loved. And so I asked him, “Stephen, I know who you are. I’m just wondering if you have any advice for young people?”

He didn’t miss a beat. “My advice to young people? Don’t take any shit from a machine. And you really nailed it with that BBQ. Thanks for that.” And with that they were off to wherever the day took them.

It’s hardly a unique perspective, but the attitude behind that advice bored deep in my brain. Partly because I understood Gaskin’s life’s work, and he’s no reflexively anti-tech granola guy. He was an early adopter of desktop publishing and the internet, definitely saw how tech could and should support a better world for all.

But the point that machines work for us, not the other way around feels super prescient again today. Obviously there’s the recent surge of buzz around AI, but I think also the broader trend of people not necessarily understanding how tech works but still being at its mercy. A generation that has grown up knowing that the shiny screens they tap at are the keys to unlocking the world, but not necessarily understanding any of the how (or why) behind it. I feel like it’s an especially important time to bring that vibe back around.

The menace of technology as I see it is not that the software itself takes over, but that it enables bad human decisions, and obfuscates responsibility for choices. We already have a lot of buffering around how we manage our industrial policy which lets people displace responsibility from themselves to “the market,” but the potential to up this game with software you can label “AI” is potentially a quantum leap in ducking accountability.

In a moment where there’s buzz about chatbots, it’s worthwhile to remember the OG Eliza, which was written in 1966 by a Computer Scientist (and Holcaust survivor) named Joseph Weizenbaum. It was a simple algorithm, just reflecting your input back to you as questions, but people went wild for it, and Weizenbaum was deeply shaken by this. He realized that it didn’t really matter what kind of intelligence was inside the software, but much more how people reacted to it. That's what determines its impact.

He correctly foresaw the potential for people to put computers in charge of decisions they don’t want to personally make, with the full knowledge of what the outcomes of those algorithms will be. It’s not god-like AI taking over the world, it’s 1000s of Lumberghs using “AI” as an excuse for whatever nonsense they’re up to.

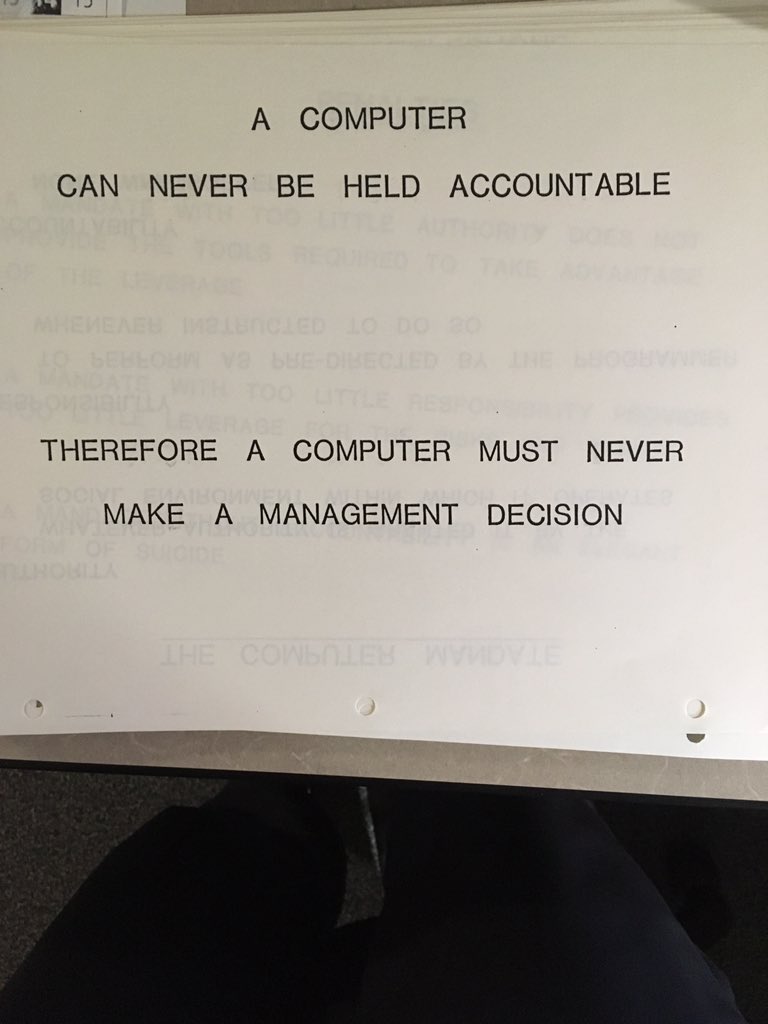

It calls to mind the (possibly apocraphal) 1979 IBM training manual that said computers should not be allowed to make management decisions:

The song remains the same, friends. Don’t take any shit from a machine.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 57.95 KB |