The Challenge / "I'm Long On The Internet"

I don't doubt that the Earth, the miracle of life, and probably even the human species have a long future, but our particular mode of living seems not long for the world. When you stop and think about the challenges that we're actually facing, and then you take a look at what we collectively invest our time and energy in, it's hard not to feel discouraged. This is what I'm referring to when I say there's an "undercurrent of doom" out there. I preach a dark future, etc.

Except really I don't. Apocalyptic thinking is contagious but ultimately not very insightful, and dispair has the downside of being both depressing and ineffective. Knowing is half the battle, so one place to start is thinking about the challenge.

Human Trouble

I think of things in very human-centric terms. While the preservation of the natural world is important, I presume that human life is probably the highest value thing we have. I don't really feel the need to deeply justify that assumption — if you disagree, we can agree to disagree — but it's generally worthwhile to start with axiomatic assumptions, and one of mine is that life is holy and every moment precious.

The main problem we face is the transition from what felt like a large world to what now feels like a very small one. This has as much to do with the ease of transportation and communication — the emergence of globalization — as it does with population growth. But the outcome is the same: our parents grew up in a world where things were much more strongly rooted, and a few hundred million first-world winners enjoyed consistently improving standards of living.

That system is failing as we transition to an order of magnitude more participants and the influence of nation-states begins to dwindle. Add the likely event that at some point in the next 100 years we'll experience ecological changes that disrupt our ability to live in the ways we've become accustomed to, and it looks a dark future indeed.

I could spend all day citing instances of how this meta-problem is growing ever more pressing, and the ruinously wasteful distractions that we seem hell-bent on pursuing instead, but really all you need for that is to scan cable news for 15 minutes. QED.

Staying focused on the challenge through all this chaff is somewhat more difficult, but ultimately more rewarding.

Making A List, Checking It Twice

When I begin mentally filtering the problems I see, I'm immediately drawn to one of my favorite psychological models — the pyramid of human needs — as an intuitive analog. Briefly, Maslows Hierarchy (the pyramid) starts with a base level of physical survival needs, and proceeds through four other layers (safety, belonging/love, social esteem, self-actualization) with the notion that you have to address one layer before "moving up" to the next.

I'm tempted to apply this same frame to humanity's problems, beginning with natural resource scarcity, and proceeding up to the nearly-Roman cultural and intellectual decline we see at the "top" of most modern societies. However, upon reflection, this is more a force than a fit, and also obscures the interdependence between our issues both in cause and (potentially) in solution. Accordingly I'm going to address the major problem-sets (as i see them), noting their inter-relationships as well as I can.

Scarcity

I don't subscribe to doomsday scenarios around scarcity — peak oil, peak soil, etc — but that's not to say there aren't real problems here. We have a massive energy deficet, with no real solution coming. A typical "first world" lifestyle, even one led with Northern European efficiency, requires a few thousand watts per person per year. We can certainly waste less ("we" in Estados Unidos especially), but it's very hard to see how we can keep our lifestyle with the 80% or so reduction in energy consumption required to make it globally viable. The rest of the world rightly doesn't see this as their problem, wants our lifestyle, and is trying to increase capacity.

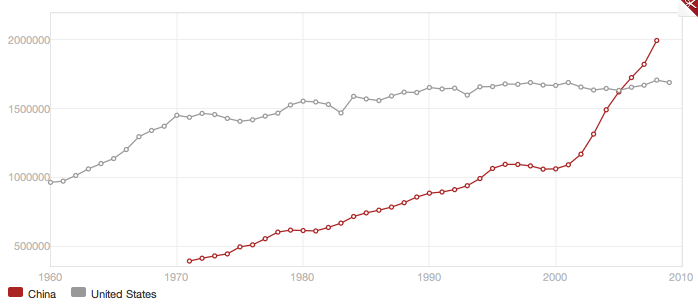

We need to more than double global energy production if we want universally high-quality standards of living. This is an obvious problem, but also a very hard one, and not one that I really see anyone addressing directly, other than China, which is doing so by consuming hundreds of millions of tons of coal a year now, with all those secondary effects for health and environment:

US vs. China Total Energy Production

Source: World Bank

Problem is, this is still not enough:

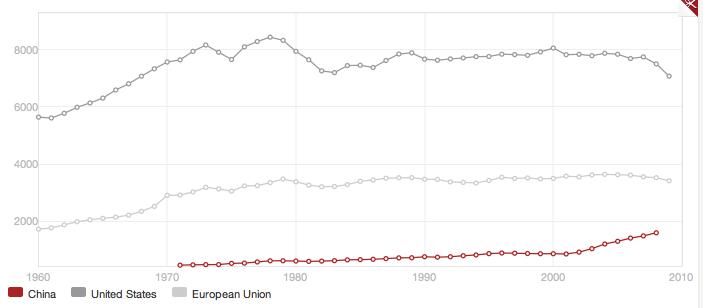

Per-capita energy consumption, US vs China

Sustaining current output over the next 100 years, let alone continuing the rapid expansion (graph #1) they'd need to get close to even European levels is pretty much impossible with non-renewable resources. There's only so much of yesteryear's sunshine (aka coal) to be dug up and burned. Remember: these stats are just China. There's another couple billion people who want in on the good life too, they're just not getting after it so quickly.

Without a breakthrough, current growth cannot be maintained. Without continued growth in energy production, the development of up-and-coming nations will run into real problems, which will be bad for everyone. Fear of this basic scarcity is also a root cause for a lot of other globally anti-social behavior.

Problems if Distribution

Looking beyond the basic energy problem, many things that look like scarcity issues are actually problems of distribution. In spite of widespread hunger, we grow more than enough food. Countless lives are consumed by the quest for drinkable H20, yet cheap water treatment solutions exist. The list goes on.

Sometimes these are literally problems of transportation or access, but more often problems of distribution are social. Famine frequently occurs in close proximity to plenty, which is only possible because people are organized in such a way as to prevent mutual-aid, or, if you prefer, to enable oppression and inequality.

It's also not just a base-resource problem. I would argue that the massive misallocation of capital represented in the Bush Era US housing bubble is another example of this phenomena. The result is a huge number of empty homes, and a spike in homelessness.

All of this this is of course morally repugnant — humans without food, water, and shelter are a collective fail for the species — but also worrying from a practical standpoint. The inability to organize the effective distribution, allocation and use of resources means we have an inefficient and fragile system, vulnerable to shocks such as drought, war or natural disaster.

Much of the field of economics is devoted to the study of this problem, but here in the twilight years of industrial-era capitalism there's a dire shortage of ideas about how all this should work. Master plans and command economies have been largely discredited, but so has "the invisible hand" of the free market fairy. The profession continues to reel, with most analysis concerned with immediate problems of mass unemployment (or fears of inflation) rather than the crumbling foundations of the whole labor/captal system itself.

Inequality, More Specifically

Surrounding the waste, inefficiency, corruption and moral failure of dysfunctional organizational systems there is the more specific human condition of inequality; the haves and the have-nots. This is not in and of itself a bad thing: perfect distribution of resources is impossible and even undesirable. Some people care more than others, and there will always be people on the up or downswing based on various measures. However, the range of inequity is a huge concern, as is its increasingly institutionalized character.

I would argue that we are witnessing the development of a global aristocracy, and that this isn't good for any of us. The wiser of the neo-aristocrats realize this, which is why you see some of the worlds most wealthy and successful individuals engaging in major acts of philanthropy. But private charity is nowhere near enough. Left unchecked, we'll end up with an intellectually moribund and socially insular leadership coterie with few incentives to care very deeply about the other 99.9% of the species. We're almost there in the US, but this is happening on a global scale as well.

And once again it's more than a moral issue. Even with the best of intentions these people will blow it. There's simply no way a small sliver of the population can be as effective as a globally engaged populous. Too many idle brains, disconnected from the real action.

Worse, there's no guarantee that any sort of breaking or tipping point will come in your or my lifetime. We have never seen levels of inequality like we have today without widespread social unrest, but that doesn't mean social unrest is a given: a new global equilibrium of serfs and lords could emerge. Stability could easily become stasis. The dark ages in Western Europe lasted several centuries, and some Eastern dynasties kept the status-quo in place for longer. Don't think it can't happen again.

Cultural and Intellectual Decay

A key part of maintaining intrenched inequality is keeping the proles in line. Historically this has been attacked from all sorts of angles, and there's a reason it's popular to reference the latter days of the Roman empire when talking about the contemporary scene. Maybe bread-and-circus will continue to carry the day, or maybe we're headed for a new proto-confucian ideology of obedience and self-sacrifice. Either way, for the aristocracy to gel, people need to be distracted from the world's problems taught to accept their place, taught to accept the place of others both above and below them.

So we see a dwindling commitment to widespread education, widespread opportunity, widespread awesomeness. A narrow and selfish attitude prevails. People look out for their own interest, or perhaps that of their family or immediate social circle. There's a general sense of being hunkered down, pessimistic, cynical.

At the same time, educational institutions produce people who know how to operate the current system — lawyers, bankers, engineers — but typically lack the critical capacity to question its basic assumptions. Research and development is stagnant. Our inability to face the challenge an integral part of the challenge itself.

Existential Crisis Beyond Politics

It's important to realize that all these core issues are well beyond politics. Certainly our current political culture isn't helping, and I personally don't see how we have a happy outcome without large-scale coordinated action — the type of thing that has historically required governments — but politics is a means. An important means, but not an end. It's easy to forget that.

In the latter part of the 20th century, the global balance of power shifted dramatically with the end of the Cold War. For all intents and purposes, the world could be fully integrated for the first time in three generations. Since the Rooskies lost that one, the presumption was that market capitalism was the winning formula.

This has turned out to be untrue. The West outlasted the USSR, but their (our) model was full of flaws, riddled with corruption and waste in execution, and clearly can't scale globally. We are headed towards a deep existential crisis as the forces of development and growth run into the reality that it's very hard to imagine three billion decent jobs in the world, and consumerism as a driver just doesn't have legs.

Ultimately the problems of humanity have the solutions of humanity. In one future we re-imagine economics as the challenge of effectively piloting Spaceship Earth, bringing more educated minds on-line to solve our fuel problem, working together in more effective ways to manage resource allocation, rethinking the social contract on a global scale, figuring out how to reward creation and create a durable prosperity that can be shared among the entire human family.

The other way is the Dark Future, in which the work is in stabilizing the unsustainable, locking in inequity and developing a global class system. I doubt many people would consciously sign up for that project, but it's what we'll all end up working on if we don't think beyond the next fiscal quarter or presidential term.

History doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme. The last time we had a moment like this in the US, it took a New Deal and a national mobilization for war to reset the economy. More war is unthinkably ruinous at this point, and individual national efforts at strengthening social safety nets (which are probably advisable, even though in most places the opposite is happening) wouldn't even begin to address this existential crisis. Big problems require big solutions and there's no time like the present to get the ball rolling.

"I'm Long On The Internet"

The fronts of the challenge are multiple, and it's not as though we have to pick one or the other. I'm still a ways away from having a coherent theory of change, but I'm increasingly convinced that the small-bore debate over national priorities, while important, is whistling past the graveyard. The challenge is a human one, not a national one. How do we conceptualize and work on that? Interesting question.

My fuzzy answer is that I'm still (as I heard someone put it this week) "long on the internet". The problems of humanity have the solution of humanity, and we've got this historically unique opportunity to get our act together in ways that were completely unthinkable a decade ago. I have a lot of hope for my generation coming up, and probably the most exciting thing about what I do for a living is being a small part of that much larger story of how we're re-wiring the world.

This is admittedly orchestrating for change in mimetic ways: I'm two or three times removed from The Change I Want To See, but shadow theater is the best I can do for the moment. I believe in the strategic direction we're headed, and trust that tactical opportunities will continue to present themselves. Unsatisfying as that is sometimes, it'll have to do for now.

Updated to fix some language bugs and add the EU to the second graph.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 31.09 KB | |

| 28.61 KB | |

| 34.98 KB |